The following is the talk I gave at last week’s Landscape Architecture Foundation Symposium in Washington, D.C. You can view the recorded talk here.

During fifteen years working and living in Los Angeles I’ve visited, studied, and helped to design landscapes for at least two dozen LA Unified School District public schools. For twelve years, my children attended (LAUSD) schools. As they reached high school, like so many of their peers, they suffered from stress, anxiety, depression, and bullying.

While I’m sure they were planned with the best intentions, the design of their schools—both inside and out— failed to support their mental health and well-being. They, and all of our teenagers, needed and deserved high schools that would guide them into adulthood with empathy, support, and love.

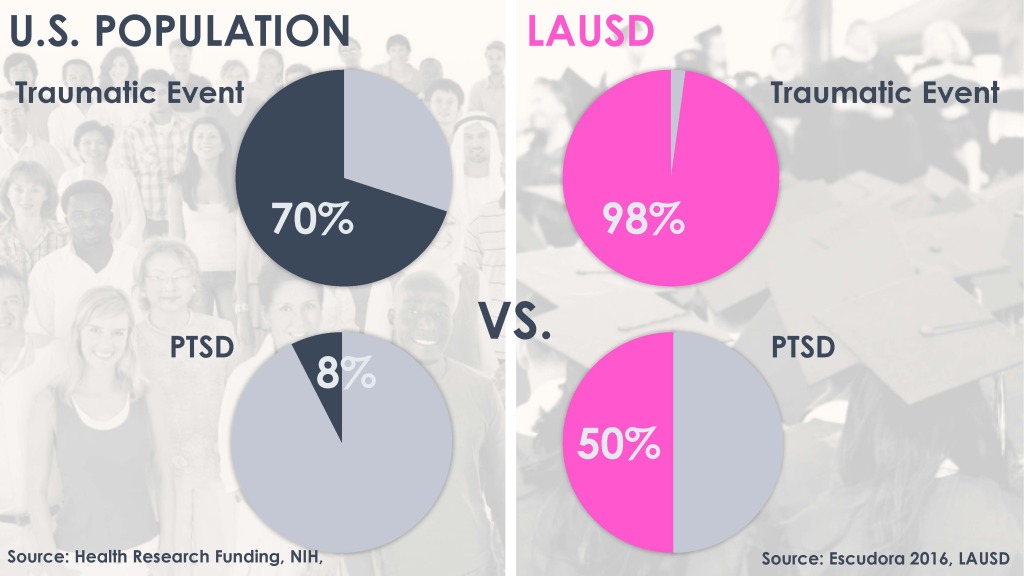

Urban communities are beset by air pollution, light pollution, and noise. LAUSD Director of Mental Health Pia Escudora reported in 2016 that fifty percent of the district’s students suffer moderate to severe post-traumatic stress disorder from family and neighborhood traumas like the death of a loved one, poverty, a parent suffering addiction or incarceration, or gang violence. These students, along with the growing number of students diagnosed with attention deficit disorder, sensory integration disorders, and on the autism spectrum disorder are hyper- sensitive to noise, light, and visual chaos.

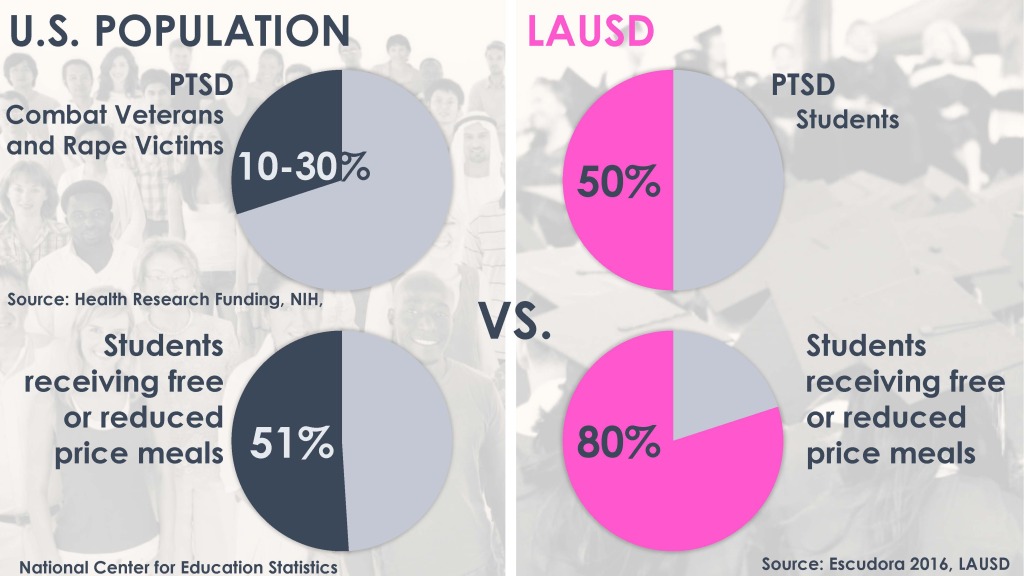

To put this in perspective, 10-30 percent of combat veterans and rape victims suffer PTSD. Of the nearly 650,000 students attending Los Angeles public schools, 325,000 suffer PTSD. Add to this startling statistic, that 80 percent (well over half a million) of district students qualify for free or reduced cost meals. Designing school grounds to mitigate these traumas will help all who study, teach, and work there.

For the past year, with the help of the Landscape Architecture Foundation, I’ve studied opportunities to leverage high school environments to support students’ mental health and well-being. I’ve found solutions that can be applied not only at LAUSD, the second largest school district in the United States, but to urban schools everywhere.

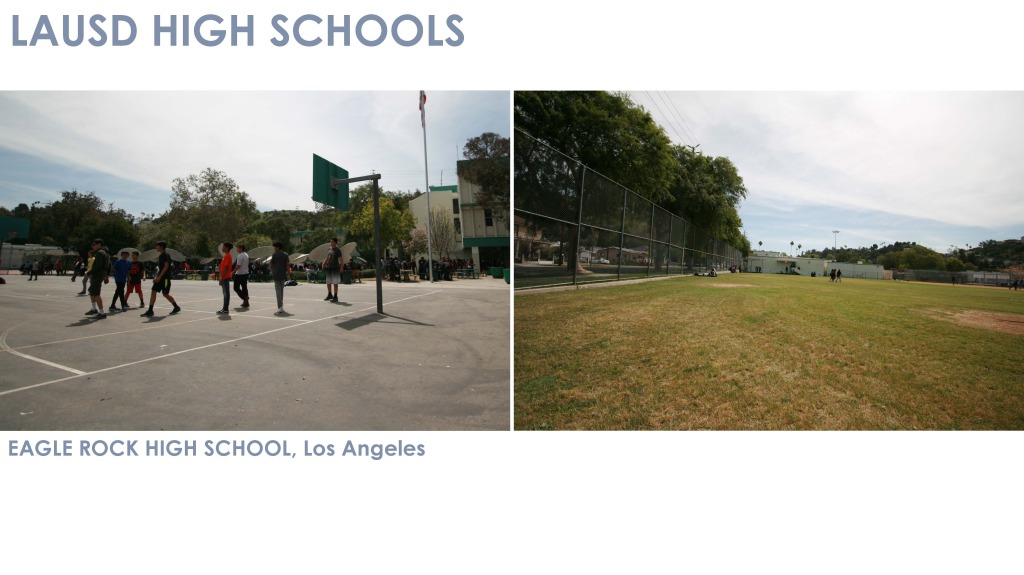

Los Angeles campuses that were once planned and designed with open and welcoming entries, generous lawns, and large gardens were slowly eroded by pressures of a growing school population, auto-centric planning, concern for security, and shrinking maintenance budgets.

Last year, LAUSD finished a $20 billion effort to build 131 new schools in Los Angeles, in order to end overcrowding, involuntary bussing, and year-round school schedules. While some were designed by highly regarded architects, they continue to follow outdated codes & policies which lack empathy for the students’ experiences, and prioritize abstract architectural statements, secure entries, and vandal-proof materials over student comfort, mental health, and well-being.

And many more campuses remain physical manifestations of decades of neglect. I ask you what message are we sending the students attending these schools? After the bond-funded build-out, the district budget doesn’t allocate enough funds to renovate and maintain all of its school buildings and landscaped grounds.

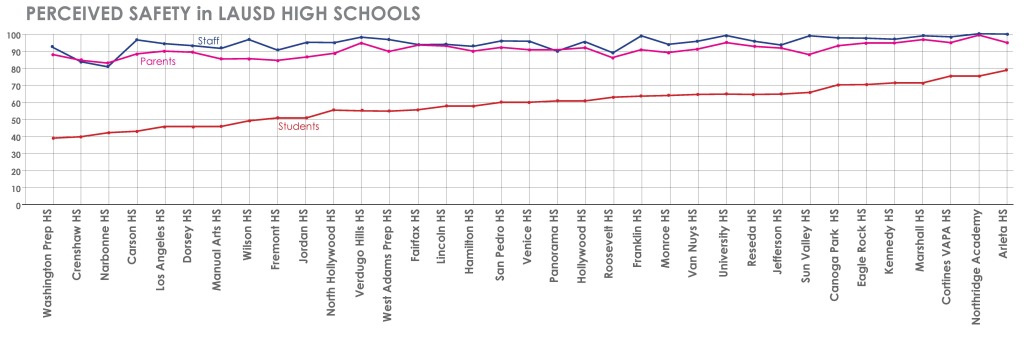

Perceived Safety

LAUSD’s annual School Experience Survey asks students, parents, and staff questions about educational goals, supports, and expectations. The graph below of 44 Los Angeles public high schools represents how many students and staff agreed or strongly agreed to the statement, “I feel safe at school,” and how many parents agreed or strongly agreed to the statement, “My child is safe at school.” As you read the graph to the right, even in those schools where students feel the most safe, the number of students feeling safe remains over 15 percentage points below their parents and teachers. It is clear that teens feel markedly less safe in their school than the adults in their lives.

We can point to at least one reason why this is true. Neuroscientist Dr. Frances Jensen switched her research from infant brains to teenage brains when her sons hit adolescence. She writes in the Teenage Brain, that as adults the hormone tetrahydropregnanolone (THO) modulates anxiety … teenagers have that same hormone, but in their brains, it amplifies anxiety. Teenagers are physically wired to feel greater stress and anxiety. So, the same stressors that impact all people living in urban neighborhoods — mainly associated with sensory overload — are more troublesome to teens.

Schools can mitigate this problem with better design to make students feel safe.

Unlike programs that rely on teachers or staff to identify students in need of mental health intervention, physical school improvements provide equal opportunity to help everyone who uses the school grounds. This idea—that school environments can improve one’s mental state —is not new but it is rarely included in discussions on how to support school safety and the lives of teenagers.

Attention Restoration Theory

Fifty years ago, psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan began working on Attention Restoration Theory, positing that the restful attention paid to leaves moving in a breeze, sun glinting off of water, birds singing from a tree, or other natural scenes reduces heart rate and stress and restores attention. For the past three decades, University of Illinois landscape architecture professors William Sullivan, Frances Kuo, Andrea Faber-Taylor, and their graduate students have furthered the theory. They’ve related access to nature in public high schools and housing projects with improved test scores … increased social cohesion … higher self-esteem … reduced crime … and a deeper sense of community.

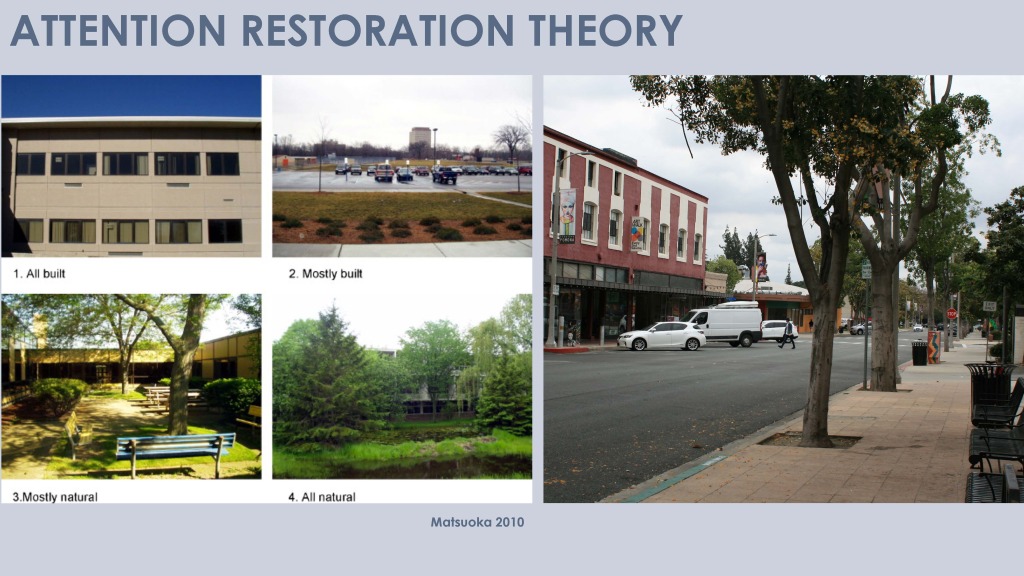

Ten years ago, Rodney Matsuoka’s University of Michigan doctoral study correlated environmental attributes in Michigan high schools with student behavior and educational success. He found that schools along high-activity streets and with larger classroom windows associate with less student crime (like illegal possession, vandalism, and violence). And natural features next to school buildings and an open campus policy associate with more students planning to go to four-year colleges.

Wide open views, on the other hand, even if they were of living grass, related to more student crime and disorderly conduct (like bullying, fighting, and insubordination); and fewer students planning to go to college. Despite decades of knowledge pointing to these impacts, exemplary models of school environments for mental health are difficult, if not impossible, to find. I found pieces … and the best examples were in Berlin.

Examples from Schools

Berlin has transformed its schoolyards for the past two decades. In addition to managing stormwater, their focus has been on reducing students’ stress and aggression. The most striking differences between these schools and those in Los Angeles are the number of small and medium-sized gathering spots amid trees and gardens. Where most Los Angeles schools maintain open schoolyards to allow easy supervision of students, the Berlin schoolyards were full of woods and plants that gave students plenty of small sheltered places where they could sit alone or with friends.

The gardens support science and arts education as well. Berlin’s school’s boasted bee hives and honey sheds … little food gardens … vine mazes … mosaic paving and sculpted benches … and small shaded seats. This “school in a garden” model is achieved with students and the community helping to plan and maintain the gardens, and with local artists who engage students to create art for the schoolyards.

Marshall High School in Fairfax County Virginia was the site of extensive school renovations six years ago. The new library is filled with sunlight and views of trees. Large classroom windows open onto a series of courtyards, one for each level, with trees and seating where students can eat their lunch outside and teachers can hold classes. Campus-wide improvements to manage stormwater became educational resources for students studying ecology and watershed health … and a source of pride when the news crews came to tour the new model green school.

In downtown Pomona, California, The School of Arts and Enterprise epitomizes the idea of a school on an active street with an open campus. It is housed in re-habbed bank, retail, and office buildings in downtown Pomona, California. The high school opened 15 years ago to serve students in a neighborhood which was known in the late 90s as “the deadliest zip code for children.” From the beginning, the school and the downtown revitalization efforts were seen as mutually beneficial in efforts to bring a downtown abandoned by manufacturing and jobs … this is an area that’s been called Southern California’s rust belt.

Students move through downtown to attend classes and galleries and theater events in four different buildings. They are free to leave campus for lunch and open classes. The students’ free movement has a number of benefits, one of the biggest being that the neighbors gets to know them, and say hello to them, and know not to be afraid of them. This creates a community where these teenagers feel welcomed and valued … I want you to think about this. Teenagers feeling welcomed and valued.

Finland, which the World Economic Forum repeatedly ranks number one in education, is redesigning its schools to support a move towards project-based rather than subject-based education. The schools are designed with quiet areas and flexible collaboration spaces replacing single-purposes classrooms and laboratories. The goal is to prepare teenagers for the workplace and collaborative environments of the present and future.

But these examples are few and far between. After half a century of research, Why aren’t there more? And what are we going to do about it? Dr. Sullivan told me, “If parents knew that green views were roughly equivalent to a dose of Ritalin, even for students without ADHD, they would demand that districts get rid of classrooms without windows and put gardens at every school.”

Six Obstacles and Responses

1. Lack of Knowledge: People don’t know … the research hasn’t left the academy. Restorative school environments for mental health isn’t yet part of conversations about school planning, design, maintenance, or school safety and mental health and well-being.

Response: It’s Time to Start a Movement. We need to share this knowledge with everyone involved in school planning, design, and maintenance … I’m sharing this work with architects and landscape architects, school administrators and teachers. And will continue writing to share with the general public … please help me share the knowledge!.

2. Lack of Policy: District and state policies don’t mandate or suggest school design for mental health. In fact many policies contradict it.

Response: We need to bring together students and the mental health, design, environment, and education communities to develop policies that prioritize students’ mental health and well-being. Working with the Prevention Institute and the Green LA Coalition, we’ll host our first Designing Schools for Mental Health workshop this fall in Los Angeles.

3. Lack of Eyes: While parent and community volunteers are common in elementary schools, in high school … that’s not the case.

Response: Nearby business owners, artists, and senior citizens can act as garden docents and informal mentors for students to add eyes in and around campus … and be there for those teenagers who might need a little extra support.

4. Lack of Involvement: During the Design process for schools, Students are not involved. Teachers and staff aren’t involved. The community is not involved.

Response: An inclusive design process that involves students, staff, and the community will better serve students and give them a sense of ownership and pride in their school. We are developing processes to survey and observe students to find out where and why they feel safest at school. Students deserve to have their voices heard.

5. Lack of Funds: The district barely has the funds to maintain what it has, let alone to renovate and add gardens.

Response: But California schools gets state funding based on enrollment and attendance. More than 80,000 LAUSD students missed three weeks last year, costing the district $20 million in lost funds. Since research shows that restorative environments reduce sick days at work, the same should be true in schools, boosting enrollment, attendance, and funding. Imagine using that money to create warmer, nurturing high school environments where teenagers want to show up?

6. Fear: These high schools were designed out of fear of vandalism, truancy, and added maintenance Costs. Yet, research shows it is access to nature, big classroom windows, and open campuses along active streets that reduce crime, disorderly conduct, stress, and anxiety.

Response: With love, we can design high schools to support teenagers dealing with trauma, stress, mental health issues, and the rest of them too. Teenagers are uniquely vulnerable to urban stresses. Public high school is the last chance to build trust, hope, and community before young people become independent adults.

Transforming Teen-dom

Transforming the way we treat our teenagers will transform the way they think of themselves and the way they interact with the people and neighborhoods around them. Restorative high school environments can invite and build a broad community around our adolescents; improve the quality of the neighborhood; reduce teenagers’ anxiety and aggression; and make them feel safer, more hopeful, and whole. With love, we can provide school environments that nurture the future stewards of our public realm and our planet. This is the atmosphere that all of us, especially teenagers, deserve.