I’ve been obsessed with the Eagle Rock High School horticulture garden for years now, for many reasons. Partly because it is a beautiful example of designing with nature. Its walkways and little walls were made with reclaimed materials. It is softly sculpted to direct rainwater from paved areas into planting, from high places to low. It has native oaks that attract butterflies and birds and cover a large part of the garden with luxurious shade. Like the mature trees dotting the wild hillsides above, its oaks and pines and flowering shrubs and vines were planted by generations of students. The garden isn’t pristine. But it is weathered and worn like something well-loved.

The first time I saw it I was a little overcome. In awe that the garden existed at all—a remnant of a time when public schools boasted wood shops and mechanics and photography labs as well as these gardens. But I was also stunned. Because I had been to the school plenty of times before and never knew it was there. This was the school my children attended on and off for years. All three of them were there for a year or two. But it wasn’t until they were gone that I first got to see the garden. It was rambly and wild, a little overgrown from a decade without a trained horticulture teacher. And I felt a stab of jealousy at the time, that this beautiful place had not been there for my children. That they may not have even known about it. It was so brilliantly tucked away between classroom bungalows and the bleachers behind the football field. Its fences were hidden by vines and hedges.

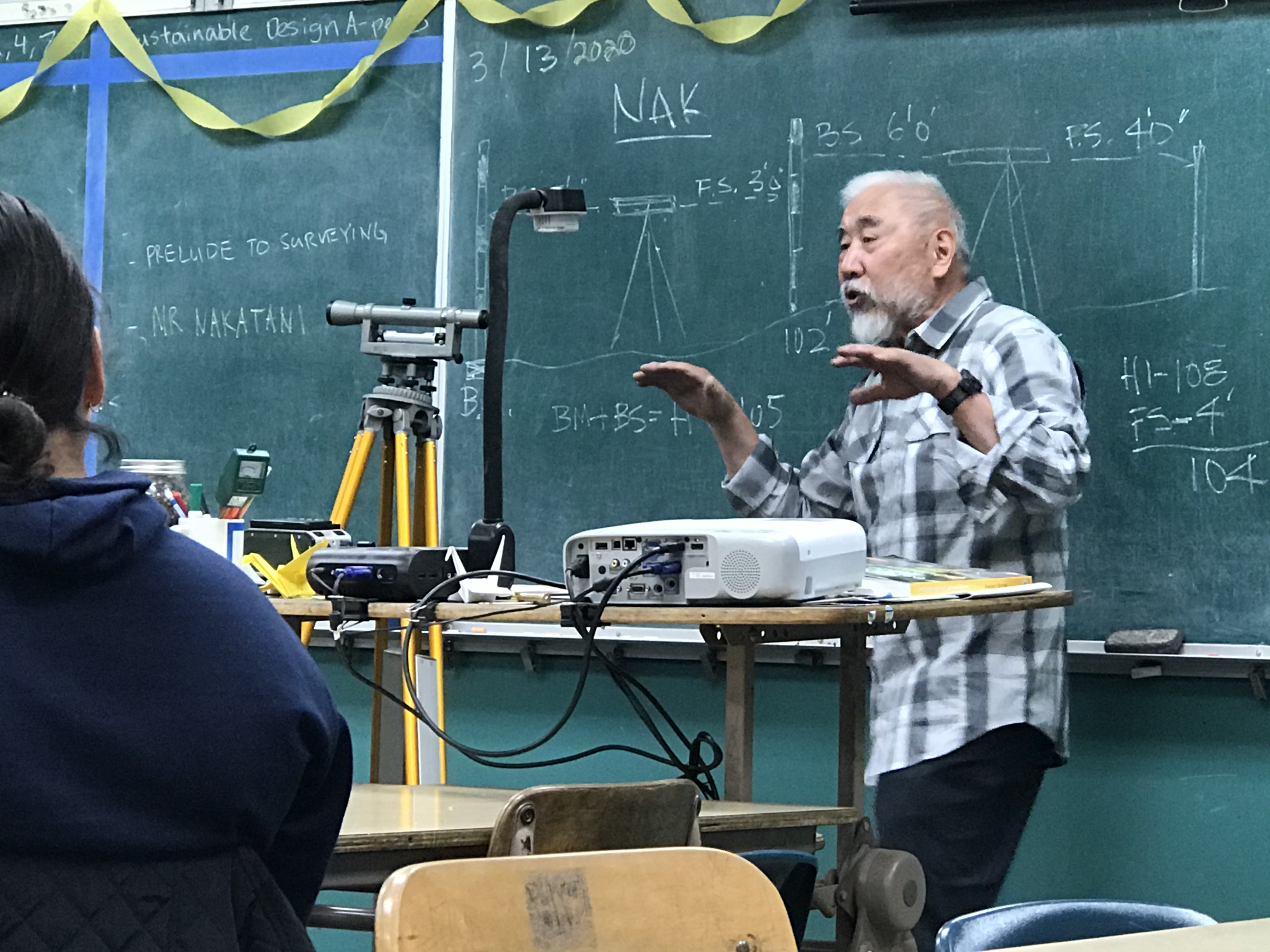

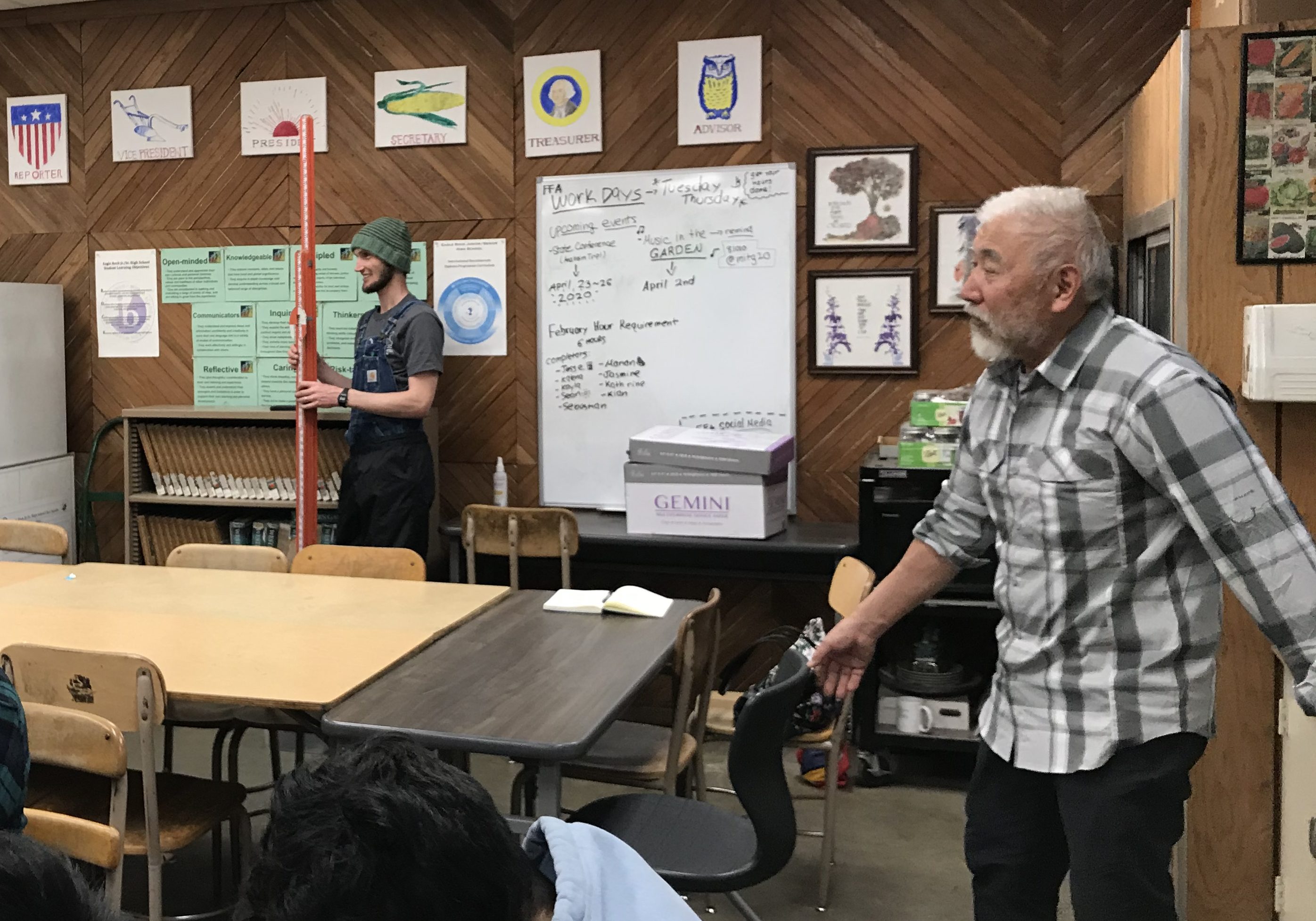

I found out about it several years ago when my dear friend Amanda introduced me to the garden and the past teacher charged with maintaining it. Trained in special education, the teacher had no formal training in horticulture, landscape architecture, or plant science. He did the best he could to keep it going … and growing. It was a joy then, to visit Friday and see it returning to full use. The new horticulture teacher, Jeff Mailes, had invited a special guest to teach his students the basics of surveying. Willie Nakatani taught horticulture at Eagle Rock High from 1967 through 2004. “But don’t call me Mr. Nakatani,” he told the class when he got up to give his lesson. “Nak is what everyone calls me. Even going through the office today, people said ‘hey Nak!’ It was like I never left.”

Between his demonstration and answering questions, Nak sits with me at a table in the corner and tells me about how it used to be. When he taught horticulture, out of the 43 high schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), 25 had fully operational horticulture gardens with two or three teachers running each one. Nak taught six horticulture classes and a science class. And he organized the students for the annual LA Beautiful competition held among all high school horticultural teams. The garden and program at Eagle Rock is now being revitalized, thanks to Principal Mylene Keipp hiring farmer, regenerative designer, and environmental educator Jeff Mailes.

It was Jeff who described so well the need for more of these places and programs today. In an age of increasing pressure to pass tests and decreasing programs that support real life skills, many young people grapple with the meaning of it all. Jeff went through something similar in college.

“I got into farming because it’s a real good zombie apocalypse skill to have,” Jeff said. “I was thinking about dropping out and growing my own food gave me a sense of security. And now I give that sense of security to my students.”

Jeff’s work in the garden exemplifies so many of the strategies we can use to support students’ mental health. Inviting Nak to teach him and the students surveying connects the students to their school’s past and connects Nak and his knowledge to a new generation of environmental stewards. The students are restoring the gardens with Jeff’s expertise guiding them, reconstructing walls, cleaning out the ponds, turning organic matter into compost. Revealing the path of water in the old creek bed that is now a fire lane is one of his many plans to bring nature back into the school’s consciousness. He leaves the gates open at lunch and during breaks, inviting students in to sit or study or volunteer. It’s become a respite in the middle of an urban campus, and a connector of generations and skills. Food grows in rows in the one sunny spot in the center. The lathe house is back in perfect shape, and the glass house is next on his list.

The students are notably engaged, following Nak’s instructions and volunteering to “read” the surveying scope. This in spite of the day it is: Friday, March 13th. Just as their class ended the LAUSD school board announced schools would close for the next two weeks, joining the growing wave of closures aimed at preventing further spread of coronavirus. Cal Poly Pomona, where I teach, had made the decision two days before. In his announcement to our students, Department Chair and Professor Andy Wilcox wrote: “As cultural, institutional and educational facilities close all around us, our public spaces, public gardens and public lands remain open. It is in these spaces that we might find some solace and respite from the anxiety of this current situation. In looking for social distance we may find a little time to close the distance to our natural world and reconnect with many of the experiences that brought us all to landscape architecture to begin with.”

And here is where the main reason for my obsession with this garden lies. Because this garden, and the few others like it that remain, provide a tremendous emotional resource as well as numerous ecosystem benefits. The sense of calm and groundedness we get from being in gardens and nature heals us. We can trace mountains of evidence all the way back to Roger Ulrich’s 1984 study on views from hospital rooms. This garden isn’t about testing and competition and making the grade. This garden is about growing and evolving and nurturing the mind, the body, and the natural systems we depend on to survive. For a deep look into the research, read Rachel and Stephen Kaplan’s and Robert Ryan’s With People in Mind, Richard Louv’s Last Child in the Woods or Sarah Williams Goldhagen’s Welcome to Your World.

What our students and communities need now, more than ever before, is for us to take the urgent action necessary to heal them. My graduate design studio is working with three local schools and their students to create campus landscape master plans that will incorporate regenerative design strategies to:

- Improve air, water, and soil quality

- Harvest rainwater, renewable energy, and sustenance for people and wildlife

- Increase the physical, mental, and social health of students, teachers, staff, and community members

- Act as community resilience centers during moments of personal or community crises

- Support educational success and workforce readiness

Every school and every community around every school deserves a community-based, nature-based plan designed to heal our bodies, minds and ecosystems. Every student deserves an appropriate and healthy learning environment. And they deserve to be involved in the design process. We may be in the midst of social distancing. But we can still plan and design. We can still organize and communicate—albeit at a distance. We can ask students what they need and want. We can work to change school policy and devote more funding for gardens in every school. We can remake our schools and communities to support mental health and resilience before the next health or climate or infrastructure emergency. And if we do, maybe the chances for “a next time” will be a little bit smaller.