Restorative Landscapes for Restorative Justice

During over a decade of personal and professional experience with Los Angeles public schools, I’ve struggled to understand the impacts that school landscapes have on our children’s hearts, minds, and bodies. So, I was thrilled to be selected as one of four Fellows for the Landscape Architecture Foundation’s first Fellowship in Leadership and Innovation to advocate for changing school landscapes. Each of us will receive $25,000 to support twelve weeks of work on our chosen topics over the next year.

We finished the first of three short but intense residencies in Washington, D.C., in May to introduce our topics to the LAF Board of Directors and mentor one another in methods and approaches. Lucinda Sanders, CEO and Partner at OLIN, and Laura Solano, Principal at Michael Van Valkenburg Associates are our facilitators with a focus on transformational leadership. With the help of our cohort and facilitators, and feedback from the LAF Board and guests Brad McKee, Editor of Landscape Architecture Magazine and Daniel Pittman, Design Director at A/D/O, a design/creative incubator in Brooklyn, New York, we deepened our original proposals. After a month of interviews, research, and deep thinking, I wanted to share an update.

Connecting restorative landscapes with restorative justice in Los Angeles public high schools.

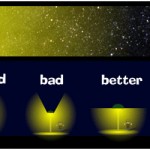

A growing body of research points to the restorative and academic benefits of trees, green views, and multi-purpose landscapes for school children. High school students in schools with green views from classrooms and cafeterias recover from stress more quickly, perform better on tests, and engage in less criminal behavior such as theft, possession, and aggressive acts (Matsuoka 2008). And yet, most school districts do not mandate multi-purpose landscapes or design to increase access to nature. Schools that do have these landscapes are located in predominantly white, advantaged neighborhoods. And even these schools often have classrooms with covered windows and policies that prevent students from accessing the nature right outside.

My own children attended Eagle Rock Junior and Senior High School, a high performing and desirable school with a great mix of students from different socio-economic and cultural backgrounds. The school has everything going for it, except design. Rebuilt after the 1971 Long Beach earthquake, the new classroom buildings are designed to prevent the protests that took place in the 1960s. There are interior corridors of classrooms with no windows to the green hills just outside. There are classrooms in older buildings with huge windows covered with translucent film that obscures the views. There are other classrooms with clear windows looking through grates into gardens beyond. The entire school is surrounded by chain link fence. Rumor has it that the redesign was by a prison architect.

Remember how stressful high school was? High school under normal conditions is rife with physical change, mental challenge, and trying to figure out who we are. In an LA School Report last spring, Pia Escudero, director of the school Mental Health Unit for the Los Angeles Unified School District, described the rates of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder across LAUSD. Compared with the rate of 7-12% in the general population, and a little higher in the military, 50% of LAUSD school children suffer moderate to severe traumatic stress syndromes. Fifty percent. Understanding that students cannot learn if they are suffering trauma, new pilot programs are being tested to treat mental health.

At the same time, LAUSD has launched a restorative justice initiative in several high schools, including Eagle Rock, to address behavior issues through dialogue and reconciliation rather than punitive measures such as suspension. Nowhere in the conversations about improving mental health and behavior is the opportunity for design mentioned.

The question I am asking this year is, where are the opportunities to connect the compelling research on the restorative effects of multi-purpose landscapes (trees and shrubs) with recent efforts to address mental health and implement restorative justice practices in our schools?

Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) is the second largest school district in the United States. What are the obstacles to implementing restorative landscapes at LAUSD schools? How can we advocate for LAUSD to update its landscape policies to support students mental, physical, social, and academic success? How can we communicate the importance of landscape to those making daily decisions that could allow students to access the restorative qualities of nature? It is time to catalyze the elevation of school landscapes in a district that can set an example.

I’m revisiting my writing and advocacy background to focus on communications to change school district policy and practices to revalue landscape in schools. I hope you’ll follow my progress, and weigh in with relevant thoughts and experiences over the next year and beyond.