Even if you don’t yet or won’t ever have a teenager, you were one once. This one is for all of you.

Teendom is a time of exploration and change and stress and too often, trauma. This year I’m using my Fellowship for Innovation and Leadership with the Landscape Architecture Foundation to look for ways high school landscapes can support students’ mental health and well-being, academic success, and environmental justice as well as the many environmental benefits healthy landscapes can provide.

While I was guiding my own teenagers through some intense times, a dear friend gave me The Teenage Brain. Dr. Frances E. Jensen, a neuroscientist studying children’s brains, switched her research to teenagers to understand her sons’ adolescence. I finally read the chapter on stress last week, and it helped explain a disturbing pattern I’ve been seeing in my research on high school landscapes. I want to share this little piece as I begin exploring solutions for better high school environments for our teens.

Jensen cites research done ten years ago on the hormone tetrahydropregnanolone (THP), which calms adults, but actually increases anxiety in teenagers. She also explains that since research on animals shows the effects of stress lasts three weeks longer in adolescent rats than in adult rats, the same is probably true in humans. Teenagers feel more stress for much longer than we do as adults.

Every year, the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) surveys its students, parents, and staff on issues to help with future planning efforts. This School Experience Survey asks a variety of questions to address topics such as positive school climate, academic expectations, school communications, social awareness, bullying, state standards instruction, and school safety. The results of these surveys are available online here.

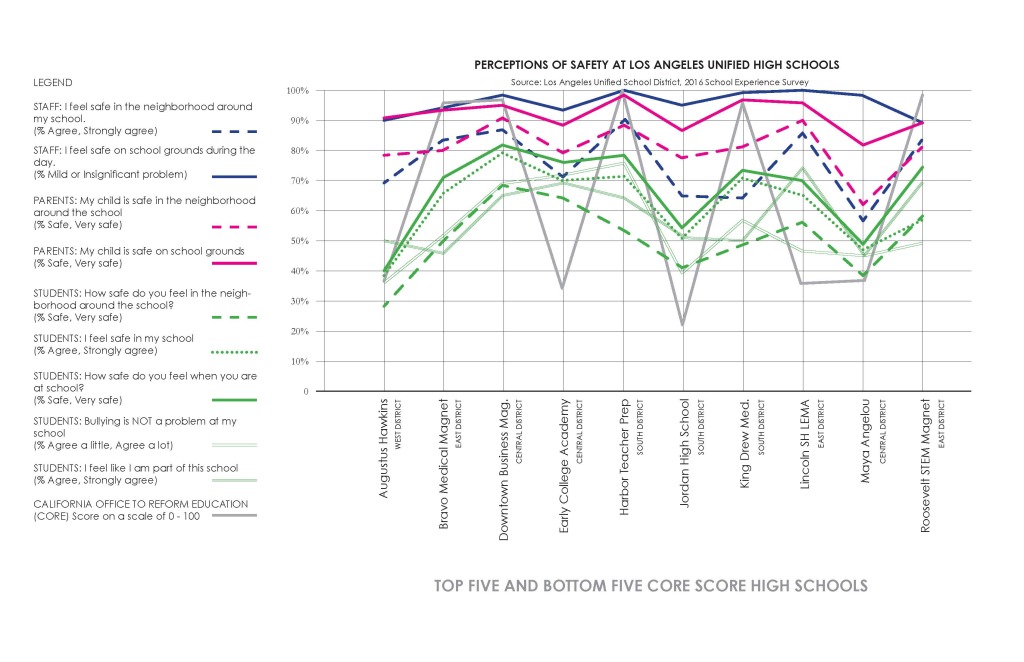

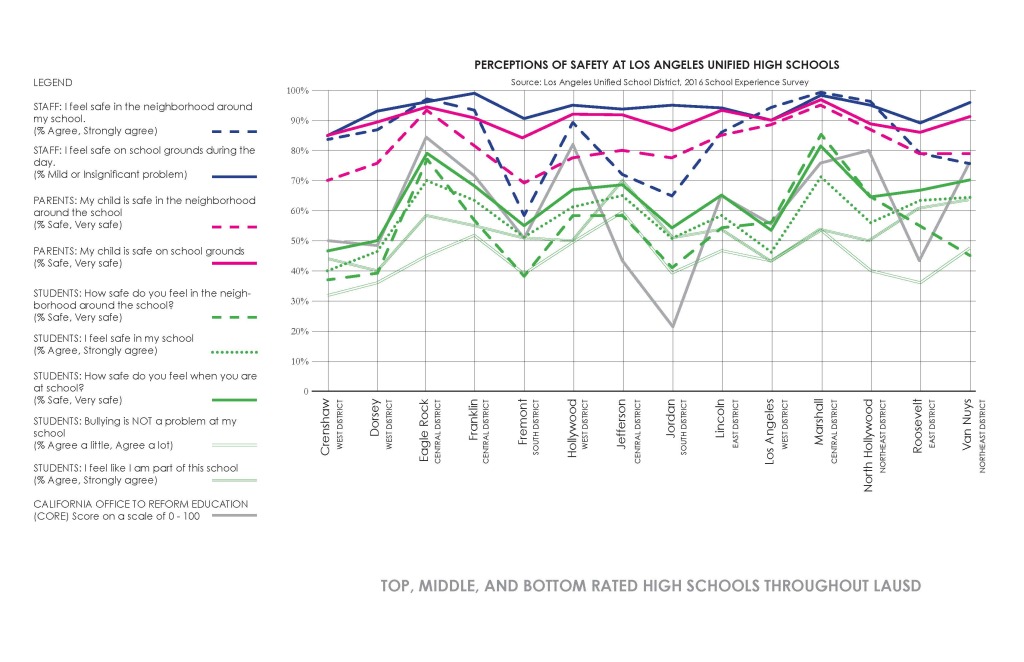

In an effort to make some sense of how safe students feel in their high schools, I graphed student, parent, and staff 2016 responses to the questions asked about safety. Because LAUSD has 96 high schools, I start here with a smaller sample. I graphed the five highest and five lowest rated schools by the California Organization to Reform Education, and then selected fourteen schools representing a range of ratings and across LAUSD’s six local districts: East, West, South, Central, Northwest, and Northeast.

Students are shown in green, parents in pink, and staff in blue. The solid line in each color represents safety on the school grounds during the day. The dashed line in each color represents safety in the neighborhood around the school. The gray line is the school’s rating, between 1-100, given by the California Office to Reform Education.

If the many lines on the graphs are overwhelming, pay special attention to the dashed and solid lines of each color. There is a remarkable chasm between how safe students feel at school and the neighborhoods surrounding their school compared to the adults in their lives. It’s not that surprising that only 38 percent of students felt safe or very safe at Fremont High School, the birthplace of the Crips, compared to 85 percent of students feeling safe or very safe at Marshall High School, that iconic school where Grease and Pretty in Pink were filmed.

If the many lines on the graphs are overwhelming, pay special attention to the dashed and solid lines of each color. There is a remarkable chasm between how safe students feel at school and the neighborhoods surrounding their school compared to the adults in their lives. It’s not that surprising that only 38 percent of students felt safe or very safe at Fremont High School, the birthplace of the Crips, compared to 85 percent of students feeling safe or very safe at Marshall High School, that iconic school where Grease and Pretty in Pink were filmed.

But it is surprising the level of safety that parents and staff feel about schools across the board, while students bring their perceptions of safety in the neighborhood with them into school. At all schools, over 80 percent of parents thought there child was safe on school grounds, and staff responses were even higher. This difference results in a 12 to 50 percent gap between how many teenagers felt safe on school grounds versus their parents, teachers, and school staff.

Teenagers so often get a bad rap. And yet, even as they suffer from extreme stress, the everyday environments of public high schools are rarely nurturing and supportive. We can change that. Rodney Matsuoka’s 2008 landscape architecture dissertation pointed to views of nature and open campuses as being the two highest predictors of high school students’ academic, social, and behavioral success. High school grounds can be planned, designed, and programmed to build community and social cohesion, improve self-worth and self-esteem, improve attention and learning, and improve physical health.

For the next five months, I’ll be gathering solutions and examples of high school grounds that break the mold to care for and nourish our teenagers’ intellects, hearts, and spirits. Please share with me any examples or solutions you might have.

And, next time you find yourself annoyed or disturbed by a teen, think about how much more annoyed or disturbed they are by the world around them.